Building Strong Communities, Pt. 1

Conversations with friends who are leading companies or working product-side often drift toward the topic of attracting business and generating revenue. We share stories, swap tips, and commiserate on what we’ve learned about making a good fit between the product and the people we’re hoping to serve.

Whenever I'm thinking about this kind of fit, my mind is often snapped back to my first real sales job—even though I've faced much larger stakes in the time since. Over two decades ago, in the summer between high school and college, I got a part-time job as a clerk at my local comic book store.

Now before you assume that job was a cakewalk, this is how I set up the scenario when I talk about the challenge my coworkers and I faced:

You’re a brick-and-mortar store in a destination shopping center with bad parking, selling a niche non-essential entertainment product with an average $3 price-point.

Now, book enough revenue to pay rent and utilities on your retail bay, pay for your product, pay your staff (including benefits), and serve people from all walks of life who wander in off the street with varying levels of disposable income and interest in your product.

Understand that you're selling in an economically-depressed city that has recently lost jobs from major employers due to offshoring.

Also, you’re selling periodical ephemera that becomes dated four weeks from release, and the public doesn't consider pop culture to be a mainstream interest (this is seven years before Rami’s Spider-man, 13 before Favreau’s Iron Man.)

Lastly, the web isn’t a thing most people do yet, so no Google, email marketing, social media, or online sales either.

I tell the story that way for two reasons. First, to accentuate just how foreign and challenging the environment of 1995 seems in retrospect; second, to highlight how tough it was to generate thousands of dollars each week by selling low-cost items.

There was also what we called the milk and gas problem—we were the optional purchase made at the end of a long list of other essential needs, so that meant we didn’t have the luxury of assuming consistent repeat business week to week. Sometimes we were in the budget, and sometimes we weren’t.

While it’s useful to reflect on how different things were then, these points all bury the lede—we pulled off double-digit profit margins against $30-40K in gross revenue each month, but we shouldn’t have been able to. When I reflect on it, I realize now that even in 1995, this was a mostly un-winnable scenario. I didn’t consciously figure out until years later that we weren’t just providing our customers with physical periodicals.

We were connecting them with a community of other people who were passionate about comics and pop-culture.

That was our central offering, not comics.

At the comic shop, I received my first crash-course on fostering and growing communities of passionate people engaged around shared interests. Then after college, I worked on a small team that built the operational core for a successful boutique ad agency in downtown Chicago. Later, I had the chance to be part of shaping the first open-source chapter of AIGA, America’s professional association of design practitioners. Amidst all of these, I’ve also done community building work with colleagues at organizations large and small, local and national, for-profit and non-profit. Between the wins, the mistakes, the moments of luck, and the many surprises, I’ve gathered a handful of techniques that I’ve seen help build healthy communities.

In this first piece, I’ll take you through articulating your vision for the community, and then we’ll look how to prove to your constituents that you’re truly committed to that vision. In part two, we’ll look at defining and addressing intrinsic human needs, working your ground game, and evangelizing the community.

Purpose and Belief

First things first: to attract and inspire a community around your goals, you’ve got to articulate what you’re driving everyone toward. What’s the big vision, the big goal, the shared purpose and animating belief behind your effort to pull a community together? The answer can’t be a lifeless, "Buy our product!", or, "Do this action!"

There has to be a story inside your vision, something about why you’re trying to move the conversation and inspire people to follow you. Sometimes it is hard to start with the belief, so start with your vision and purpose first. Then use The Five Whys technique to find the belief that is powering that purpose. Try phrases like We’re here to…(blank.), then ask why five times, then dig deep and try, We believe that…(blank.)

For more guidance, watch Simon Sinek’s TED talk or read his book Start With Why.

Four real examples of purpose and belief:

-

At the comic shop, we always said we were there to offer escapism to people who love art and stories. That was true, but there was an unspoken belief behind the way we worked: We believe comics and pop-culture can be enjoyable and educational for everyone, and we welcome everyone to be their authentic selves in our store.

-

My colleagues and I at the ad agency were all dissatisfied with our ad-hoc operations, and we knew we needed to become more efficient and adopt a company-wide way of reliably producing our work. The subtext: We believe new tools and techniques can help our team find a better way to work together.

-

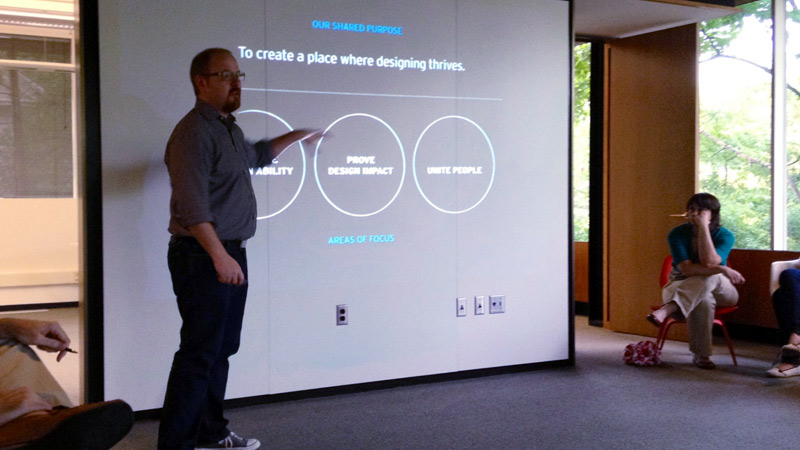

When I joined the executive board of my local professional association, AIGA Raleigh, my colleagues and I described our purpose as creating an environment where design practitioners could thrive.[1] The belief powering this vision: We believe that by raising the confidence and profile of design professionals, we can expand their career prospects, improve our city and region, and raise awareness about the profession—all at the same time.

-

A client in the manufacturing industry who hired my firm to help with an employee engagement effort to foster new product ideas said their goal was to create a culture of innovation. The belief behind it: We believe that company employees have excellent ideas for improving existing products—we'll succeed if we invite them into the company’s innovation process.

If you’re trying to define a new vision and belief to replace an old one, make sure you’re ready to address past positioning or missed expectations with potential community members. How is it going to be different this time? (more on that in a minute.)

If you’re doing something entirely new, try and contrast your big vision with any current assumptions your community may have. Once you’ve defined your big vision and core belief, you have to ruthlessly tie all of your actions, organizational structures, processes, and major decisions back to that one thing. If you’re contemplating something that doesn’t serve that big vision or core belief, don’t do it—even if this is costly to you. Once your vision and belief are out there, you have to protect them and refuse to undercut them.

Proving By Doing: The White Garbage Truck + The Twist + The Open Door

Everyone can make statements and say they’re going to do a thing. The proof is in the doing. Once you’ve put the why out there, you’ll need to start doing to show that you’re living your ideals.

Right away, you’re going to huddle with your team and map out your first 100 days—just like a new President or a Chief Executive would. How are you going to take advantage of the momentum you’ve created in your big vision rollout, and start proving that you’re making significant moves? What immediate things can you get done, and what do you need to start laying the groundwork? Make a list of tasks you and your team are going to knock out in the first 100 days, and include three things: visual symbols and physical tokens, a surprise that proves your total commitment, and public ways you’re going to share your work and invite conversation.

The White Garbage Truck

Start by putting symbols of change out there as quick as you can, and find a way to make them things people can touch and see. The reason is, many well-meaning and hard working community leaders come in and make a common mistake: they focus immediately on heavy-lifting work that is done out of the public eye, leaving nothing tangible for their community members to see.

People need to see progress to believe in progress, even if the things they can see aren’t necessarily the highest value things. The absence of a visible story backed by tangible artifacts creates a void at the beginning of your new efforts, and incorrect or false narratives can quickly fill the space if you don't take swift action.

My friend Matt Muñoz, who led our AIGA Raleigh board during a time of major change, always talked about the need for these immediate symbols via this story about a story:

One of (my) friends likes to tell a story about a small-town mayor. Once elected, amidst all the other priorities, the first things the mayor did was to paint all the town’s garbage trucks white. Citizens noticed the immediate impact and said, “This town is really turning around! Do you see how clean the garbage trucks are?”

That buzz about how “this town is turning around” is vital. You’ll capitalize on that energy to help support work that is more challenging, and you’ll more easily enroll people into your community who were excited by those first changes. Now, if your entire way of proving your dedication to the big vision and the shared purpose is purely cosmetic, that will lose its efficacy over time, so you have to provide more than symbols.

Four real examples of The White Garbage Truck:

-

At the comic shop, we wanted to revive the business after a speculation-driven downturn. We cleaned the place from top-to-bottom, then re-organized the product displays to emphasize great stories, brilliant creators, and staff recommendations. Customers immediately responded positively to the change as we became what's called a reader's store, not an outlet hawking collectibles.

-

At the ad agency, we created an onboarding process for new hires that publicly valued their professional development and skills improvement over immediately billing their time on client work. With extensive 1:1 workflow training and shadowing that first week, existing staff saw a new up-front investment in maintaining smooth workflow for the whole team—a noticeable change that signaled we were taking their concerns seriously.

-

At AIGA Raleigh, we changed our organization's name to AIGA Raleigh Design Community, then created a new brand that sat apart from the established look of the national organization. Looking at both the new name and how it was expressed, long-time community members noticed the change and reacted with curiosity and questions.

-

At the manufacturing client, signage is the primary communication tool to convey top company goals around safety and operations. After placing new campaign signage at the plant entryways, employees who passed these signs every day—60% of the workforce—became aware that something new was happening.

The Twist

Next, ask yourself: What’s the one significant thing I can do that will prove I’m committed to the big vision and shared purpose? You’re looking to make something big happen, to bring people together, and to move your community forward, so it helps to have a hook I call The Twist that will grab attention in a way that is practical, not symbolic. It has to be something that’s unexpected, and it has to prove your total commitment to the shared purpose beyond all doubt.

Remember that movie Miracle on 34th Street? There have been several versions made over the years because of the staying power of the story. Common to all of the movie versions is a moment where Kris Kringle stuns the management at Macy’s by altruistically sending customers to other stores if items aren’t in stock at Macy’s or if they’re cheaper elsewhere. As someone completely committed to the selfless spirit of the holiday, Kris Kringle doesn’t even hesitate—it is his primary concern over all business interests. He is going to do whatever he can to make sure children have a wonderful holiday (he is Santa after all), and that motivates him above all else.

This practical dedication to the shared purpose of the holiday is so surprising and unexpected, Macy’s customers react with an outpouring of support—and sales. Quickly, Macy’s customers lionize the company for their total commitment to a previously implied purpose (we help you and your family have a great Christmas), and Gimbal’s—the rival department store—is scrambling to catch up and adopt the same policy. For employees and customers, it is a complete surprise, totally unexpected, and now everyone is talking about it. That's The Twist.

Four real examples of The Twist:

-

Proving that we were a reader's store completely committed to great stories, we let customers borrow collected editions (called trade paperbacks) of fantastic comics we recommended, just because we wanted to expose them to the content or the creative team. No deposit required, no promise to purchase, just the right book in the hands of the right person. We used a handshake and an in-person statement of trust to ensure that they'd return it, perhaps buy it if they liked it. People were stunned by this offer, uncertain about what the catch was—but there was no catch other than getting them excited about stories. It made who we said we were, and who we were in practice, identical. In all the years we did this, I think we lost one, maybe two books that didn't come back. We sold hundreds of books this way, and we made many loyal customers too. Most people returned with a smile on their face, enrolled in our vision—a community of readers who love the medium.

-

Saying you're committed to helping people do their best work is one thing, but laying out the cash to provide them with the best tools available—that's where actions do what words can't. At the agency, new employees started on day one with a brand new computer, a drawing tablet, all the latest creative software, a fast Internet connection, and access to best-of-breed large format printers which stood at the ready to output their creations. Bosses may tell their employees they're committed to productive processes and smooth workflow, but it is unusual to have the investment so visible and immediate. At the agency, this practice turned heads while proving that giving "the best" to staff set a bar which allowed our employers to expect "the best" in return.

-

Reinvigorating a professional association around the mandate of helping people thrive in their careers, we decided that we needed to prove that promise in a tangible way that created direct impact for our community members. With a new initiative called the Pursuit Fund, we took every dollar of money we received from membership dues, and turned it right back around and gave cash grants to members who wanted to continue their lifelong learning. No one expected that, and it was the first time an AIGA chapter had ever made that kind of pledge—that every dollar received from members goes right back to the members as dollars. The Pursuit Fund was a powerful, public commitment.

-

The manufacturing client offered gift cards, prizes, and recognition to employees who participated in engagement challenges and idea generation exercises. A good start, but by no means a surprise. What raised the ante was offering paid time off (PTO) to employees who submitted ideas that were voted up by their peers. Everyone likes to win something, but PTO is additional wages—something that brings real value to people's lives. By offering PTO, the company showed that they cared about this process, and employee participation increased dramatically after that announcement.

The Open Door

Lastly, as you dig in on the slower long-term work, you need to be forthcoming in showing your process and progress. In open-source and cooperative communities, historically that’s a mailing list or a web forum. In local government, that’s the city council meeting or an open hearing. In business, that could be an all-hands meeting, team chats, a newsletter, or hallways and bulletin boards full of drawings and mock-ups. Whatever conveyance you choose, you need to start putting updates out there early and often, and folks need to understand how you're making decisions.

Whatever you think the right communication frequency is to share your work, you're off by at least half—double what your gut is telling you, right on day one. Whenever you’re wondering if a conversation or meeting should be open or closed, open it up. Default to open—its how you show hard work is happening on the road to significant change. Otherwise, people will think you’re all about white spray paint, not about the hard stuff.

Four real examples of The Open Door:

-

"Open Door" is a common phrase in business about inviting entry and conversation, but in the case of the retail comic shop, it wasn't metaphorical advice. We opened the front doors of the store on weekends and at special events to invite foot traffic and passersby into the shop. We wanted them to peek in and see something interesting, to feel welcome in approaching the entryway, and to see that there was no barrier to stepping through the portal. At the same time, they could see what we were doing—that things inside had changed. Where you're lucky enough to have a physical boundary as the barrier to showing progress, that's easy—open it.

-

When I was working to build the ad agency staff into a team that worked well together, I took what I learned at the store and brought it into the office. Not only did I always leave my office door wide open, but I also made myself available all the time to anyone who wanted to come by, call me, or send an email about anything (this was before texting.) To be transparent about the work, I shared frequent updates to the team—in-person and over email—to solicit their opinions, explain what was happening and why, and to share wins and progress. It may have been more information than some people wanted, but everyone was informed and felt included in the process of designing the new workflow.

-

Free, open meetings were the secret sauce in our recipe that revived AIGA Raleigh. First, we took an already existing practice of open monthly board meetings, and we increased the frequency while moving to a more accessible location. These monthly board meetings in an office building boardroom became a weekly meeting held in a downtown coffee shop. Anyone from the community, member or non-member, could join us each week to observe the discussion, hear how we made decisions, pitch their ideas, give feedback, and watch how our work got done. In conjunction with that, we created a new monthly event—the open Community Meeting. With the business of the board being done at the coffee shop each week, these large public meetings were produced events where we shared recaps of past events, promoted upcoming events, asked for volunteers, talked about goals, and invited the community to give feedback and direction.

-

To show manufacturing employees that the company was committed to the product innovation process and that their feedback was vital to the success of the organization, project leads did two things to "open their door." First, they regularly flew field sales and line-work manufacturing employees to the main office to participate in cross-departmental product innovation workshops. Second, they traveled regularly to each of the company's far-flung manufacturing campuses, including remote locations that rarely received visits from HQ, and hosted town hall conversations where they showed work-in-progress and solicited feedback on product ideas. These in-person interactions helped prove to employees that significant work was happening and that their participation mattered.

So, to build a strong community, start with why you’re putting this community together, and remind yourself of what you believe. Then, on day one, get the white garbage trucks rolling with some visible changes, look for the unexpected move you can make that shows 100% commitment to your shared purpose, and start opening all your doors (and conversations) as a habit.

Next up, what people need from you, the value of being visible, and how to evangelize the community.

Special thanks to Jermaine Exum, Dan Morris, Brian Cozad, Jay Nierodzik, Matt Muñoz, Jonathan Opp, Sarah Mason, and Colby Swanson—they were my main comrades-in arms on the four projects I described above.

Additional thanks to friends, colleagues, clients, mentors, and teachers I've worked with, also to wide-world leaders who have lived by example: Saul Alinsky, Julie Anxiter, David Blue, Stephen Brown, David Burney, Donald Crumbley, Greg DeKoenigsberg, John Gilstrap, Kassidy Goodman, Ric Grefé, Laura Hamlyn, Jason Hibbets, Jason Horner, Michael Johnson, Nick Jones, Zena Jones, Mike Joosse, Rob Landry, John Loftin, Douglas Mangum, Bob Millikin, Nick Prestileo, Ryan Rubio, Studs Terkel, Kate Thompson, Kathryn Thompson, Marnie Thompson, and Cal Trumbo.

These people have shared their thinking, tidbits, and experiences in building strong communities, and I’m grateful for all the ways I’ve learned from them over the years. Any errors or omissions here are my own, not theirs.

Cover Photo © Jonathan Opp: an AIGA Raleigh Community Meeting, cira 2013.

For a deeper-dive into the AIGA Raleigh case study, watch AIGA National Board member and AIGA Raleigh Past-President Matt Muñoz present our team's work to other AIGA community leaders. ↩︎